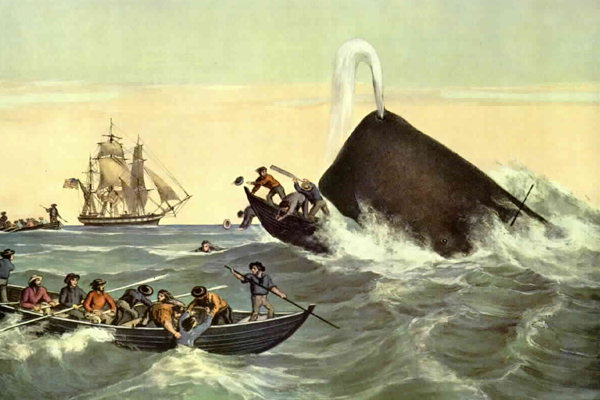

In recent centuries, has anyone been swallowed — whole, alive, Jonah-like — by a whale, and lived to tell it about it?

Last March, as Fox News informed us, “A diver in South Africa survived an experience out of a biblical passage last month when he ended up almost being swallowed by a whale. Rainer Schimpf, 51, was snorkeling off the coast of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, when he ended up in the path of a Bryde’s whale, which opened his jaws and engulfed him headfirst. The 51-year-old said once the whale grabbed him, he felt pressure around his body but soon realized he was too big for the whale to swallow him whole which was ‘kind of an instant relief.'”

Perhaps an understatement.

We’ll soon be releasing a new book, Lying Wonders, Strangest Things. Among the chapters we considered (but in the end decided not to include, for simple lack of space), was one about how there have been rumors, legends, and straight-out seafaring tales to this effect in recent centuries. The most famous occurred on a ship called Star of the East in 1891, an account that even found its way into newspapers.

A barque of 733 tonnage, the Star of the East, left New York, it seems, on June 25 of that year, bound for New Zealand.

Searching for whales in the vicinity of the Falkland Islands, a mishap occurred: as two smaller boats launched from the Star to finish off a whale, the nose of the thrashing, mortally wounded, exceedingly large mammal struck one of the vessels, throwing crew into froth and frenzy.

While doing so, they noticed, to their perplexity, a movement in the gut, and when the massive offal was slashed open, there was James Bartley — doubled-over and bleached by the gastric juices, but alive: No three days, for sure, but all too much time in what he was said later to have described as a dark, hot, slimy prison; the “curse of Jonah.”

Revived, it’s said Bartley remained in a state of traumatized lunacy for two weeks — plagued by nightmares one can only imagine. An astounding story, repeated in periodicals and books — but was it true?

As skeptics pointed out: the Star never was a whaling boat and descriptions didn’t mesh. Some said Bartley’s skin was blue, others the bleached, pale white. There was even discrepancy as to dates.

And while it could have been near the Falklands at the stated time, there was no “James Bartley” on the ship’s papers of registration, which meticulously listed crew members.

Perhaps a final nail in this legend: the wife of the captain, Mrs. John Killam, said she was with her husband the whole time and at no point during her husband’s entire tenure was a man lost overboard…

But that doesn’t mean no one has ever been swallowed by the animal, nor that the sea bears only good luck. In fact, when something unfortunate occurs out there on the high ocean, sailors call it precisely the “Jonah curse” — none a better modern example than Andy O’Donnell of Olathe, Kansas, who left his family’s farm to become a radioman in the U.S. Navy during the 1930s.

Consider his career:

After completing basic training in 1936, O’Donnell was assigned to the deck force of the old battlewagon, U.S.S. Arizona, while he waited for a job as radioman.

Nothing much — good or bad — happened aboard the Arizona, and Andy was discharged in 1940, upon which he headed back for Kansas, finished, or so he thought, with his honorable duty.

But that had no bearing on O’Donnell. He had been reassigned to the U.S.S. Lexington, an Essex-class aircraft carrier that, like the Arizona, had its port in Hawaii. To get there he was forced to hitch a ride on the U.S.S. Hammann, which left the mainland for Hawaii in late February of 1942.

O’Donnell quickly assimilated with the three thousand other seamen, but his time aboard the Lexington would prove short. During the Battle of the Coral Sea, the battleship was critically damaged by a bomb and pair of torpedoes in this skirmish that cost America more than six hundred brave men their lives.

Andy was not among the casualties, having been plucked from the ocean by an accompanying boat — the light cruiser U.S.S. Vincennes — moments after he had been tossed into the sea.

While O’Donnell awaited his next orders, the battle of Midway Island ensued. Lost in that engagement: the U.S.S. Hamman — the destroyer that had transported Andy from the mainland a short while before — taken out by a Japanese submarine.

That made three ships O’Donnell had been on that subsequently sunk.

One can be excused for lifting a skeptical brow: three ships is a lot, but then a lot of ships were sunk or damaged in that war. It wasn’t that extraordinary to have been associated with several of them.

But then came the U.S.S. Quincy, one of several cruisers sent to assist in the Marine landing at Guadalcanal.

Tragically, a day after that successful operation, a Japanese task force snuck up and sank four American ships in what has been called the biggest defeat in Navy annals. Among them was the Quincy, and half her crew.

During that same melee, the cruiser Vincennes — which, if we recall, had plucked Andy from the water earlier that year — was also lost.

Once more, O’Donnell survived! — rescued the next morning by a destroyer named the U.S.S. Wilson. But by now he had been on two ships when they were sunk and associated with three others that met unfortunate fates.

Perhaps taking note of the radioman’s ill fortune, his command assigned him to land-based duties on Ford Island until 1944, when, urgently needed, he was now placed on a vessel — a submarine — designed to go underwater!

That was the U.S.S. Bullhead.

Was he still a jinx?

Or, with the war about to end, had the Jonah “curse” likewise reached its denouement?

Alas, on her third patrol off Bali in Indonesia, a lone lingering Japanese patrol plane dropped a pair of depth charges, instantly breaching the sub and sending her to the bottom… this time with O’Donnell going down with her.

Final tally: every ship upon which O’Donnell had spent a night — six of them — was sunk. The odds against chance: exceedingly high. O’Donnell had survived two sinkings in three months, something no other U.S. sailor had accomplished… but met his fate in August, 1945, mere days before (August 5) Japan surrendered.

No Jonah, he, just an honorable, dedicated sailor… whose luck finally ran out.

[resources: ‘I Give You Authority: Practicing the Authority Jesus Gave Us; New Mexico retreat: movements of the Spirit in our time; and Spirit Daily pilgrimage, October]

</p>