We’re anything but Buddhist, yet a young guy from Japan presents a fascinating discourse on living simply—you know, like Jesus.

The story he tells is that of his nation’s dive from the second largest economy in the world (you may recall: about to surpass the U.S.) to a circumstance where its stock market (digest this) lost eighty percent of its value and has never really “recovered.”

That’s a misnomer—”recover”—because, as he argues, Japan is in a better place, in many ways, than it was before.

“People there, especially young people, don’t seem to want anything anymore,” says Louis Zhao. “Renting instead of buying homes, public transport over cars, and they seem to prefer keeping the money they have as cash, instead of investing. Many young have stopped looking for love altogether. At least forty-five percent of them have not had sex for twelve months.” Among females who’ve never married, more than half are virgins.

Sounds like the good ole days! (Or nearly.)

They call it a “Low Desire Society.”

“In Japan,” notes one author, “men and women, young and old, all suppress their desires and put money into savings to minimize anxiety, even if only slightly.”

Of course, this all started when Japan’s supercharged economy, which had been growing at ten percent a year, crashed. Japan was anything but a low-desire society back then. Highways were packed with cars, stores with people. “The appetite for new experiences seemed endless,” says Zhao. “Everyone wanted to get ahead. It seemed like the ‘good times’ would never come to an end, but all good things come to an end.”

Remind you of any place you know?

Back a few years ago, Japan’s entire landmass—which is one twenty-fifth the size of the U.S.—was four times the value. Tokyo’s real estate value was such that one parcel that the Imperial Palace, occupying just 1.3 square miles, was priced higher than all the real estate in California.

It’s called a “bubble.” In North America and much of Europe, it encompasses you.

Japan? People were buying things just to buy them. Everyone thought that everything would continue to increase in value—until it came crashing down.

That happened after the country increased interest rates, in an attempt to tame inflation.

It worked—too well. There was a downward economic spiral in the 1990s and the beginning of what seemed like terminal “stagnation.”

Real estate? That fell seventy percent.

And so on.

People who were rich on paper watched it all turn to ashes.

The cost of living is now affordable. You could argue that it’s all pessimism, but it seems more like a correction.

People don’t want things anymore.

Is what’s bad for the economy (politicians) good for spirituality?

“If I truly don’t want anything, and I’m sitting in this chair, chilling, in a state of perfect comfort and contentment, I can’t see how anyone could say I have a problem,” notes Zhao. “In fact, what I have seems like the complete opposite of a problem.”

Think about all the billionaires who seem always tense, angry, unsatisfied (even with half a dozen luxury homes), or in need of tranquilizers. In the U.S., right now, you can never have enough.

Is having no desire a problem or having (material) desire?

We have to want the right things (see: Jesus).

What did He own?

“The end of desire is the end of sorrow,” Buddha taught.

And while we don’t subscribe to his whole program, there is some truth in that.

You can get what you want or more simply, want what you have.

You can fulfill your desire or lower your desires.

It’s a choice. It’s a paradox. Some things we have to want because they are things we need.

But it’s gotten to the point where everyone is driving a mammoth truck or luxury SUV and average household debt is $152,000.

Socrates once looked at a marketplace and said, “How many things I can do without.”

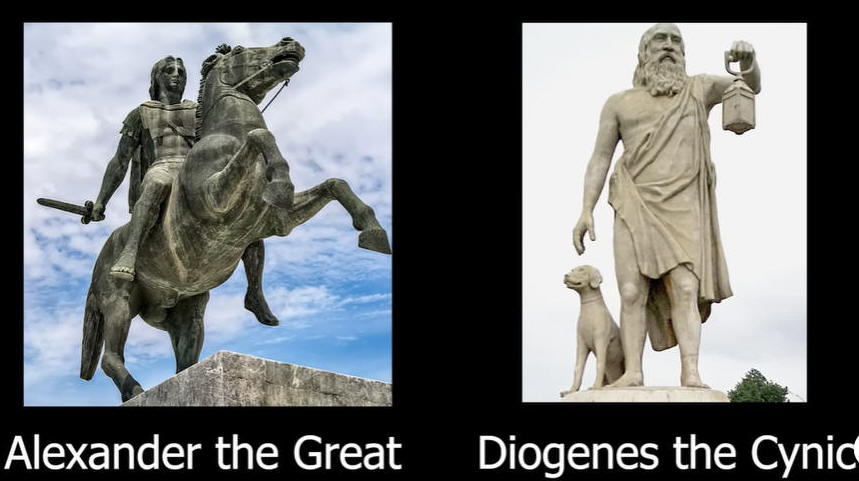

As Zhao points out, there were also Alexander the Great and Diogenes.

One has everything yet wanted more and was always at war, while Diogenes wanted and had virtually nothing (even deciding to get rid of a cup for water, using his hands instead).

Yes, these are extremes.

But also yes, we live in extreme times.

(After meeting him, Alexander the Great said, “If I wasn’t Alexander, I’d like to be Diogenes.”)

But back to Jesus:

He didn’t leave a will because he “owned” nothing, yet left us everything.