By now, even the secular world largely recognizes that there is a mysterious, inexplicable image on a fourteen-foot length of sepia cloth known as the Sindon or, “Shroud of Turin.” While scientists tried to shut it down once and for all during the 1980s, with radiocarbon dating (claiming it went back only to the Middle Ages), that critique conclusively has been found to have been in error (skewed by the carbon residue from a medieval fire).

Many skeptics now acknowledge the unexplainable pollen found microscopically in the fibers (pollen from plants that were exclusively around Jerusalem two millennia ago, along with spores or pollen known solely to Turkey and parts of France where the Shroud has been stored); and they also admit that the image was created with no known paint or pigment — indeed, not done with any known method.

Only the very tips of the fibers are darkened (where paint would soak to the bottom).

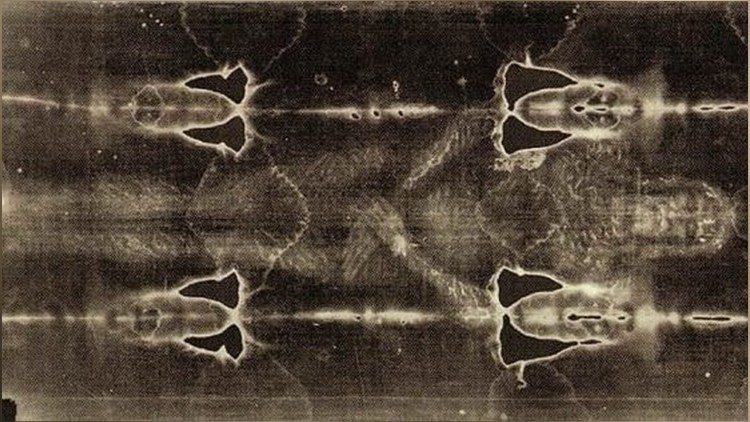

And there is the entirely stunning fact that details of the Shroud — which for centuries was venerated as having the vague, blurry outline of a Man believed to be Jesus — only came to discernible view with discovery of the camera, whereupon a negative of it revealed the curves and lines in full relief — overwhelming details.

It turned out — incredibly — that the Shroud is an image in negative.

A negative of a negative brings forth a positive.

The unanswerable question:

How could a negative image of a man get onto an ancient cloth, even if it had dated only to the Middle Ages, when photography was only invented in the 19th century?

And there was more — precise details on the Wounds and traces of Blood, even traces of coins that, as per the ritual in ancient Jerusalem, were placed over the eyes.

But back to the question:

How did the image get there?

And here we turn once more to the incredible book by Ian Wilson, The Shroud of Turin. Astonishingly, he reported, scientists have wondered if there is an answer to how the image was inflected or imprinted in thermonuclear explosions, for detonations of bombs, such as that dropped on Hiroshima, produced a flash that left prints on cement of shadows cast by the incredible flash of atomic light.

In other words, a nuclear flash can imprint a shadow. (

“The impression is inescapable,” wrote Wilson, “that, rather than a substance, some kind of force seems to have been responsible for the [Shroud] image. Whatever formed the image was powerful enough to project it onto the linen from a distance of up to four centimeters, yet gentle enough not to cause distortion in areas where there would have been direct contact.”

It all would have happened, he noted, in “a mere millisecond of time.” The “force,” one logically speculates, was the energy generated by His Resurrection.

“It was perhaps manifestation of this power which took place at the Transfiguration, the extraordinary incident described by the three Gospel writers when, on a high mountain, the aspect of Jesus’ Face changed and He appeared in brilliant light, His clothing “dazzlingly white” and “as lightning” (Matthew 17:1-8, Mark 9:2-8, Luke 9:28-26),” Wilson noted.

One reflects on a burst of energy that in the Shroud preserves for posterity what the author called “a literal ‘snapshot’ of the Resurrection.” Let that sink in.

“However the image was formed,” says Wilson, “we may well be entranced by the fourteen-foot length of linen in Turin. For if the author’s reconstruction is correct, the Shroud has survived first-century persecution of Christians, repeated Edessa floods, an Edessan earthquake, Byzantine iconoclasm, Muslim invasion, crusader looting, the destruction of the Knights Templars, not to mention the burning incident that caused the triple holes, the 1532 fire, and a serious arson attempt in 1972 [plus a more recent fire in Turin].”

It is ironic, notes Wilson, that every building that housed it before the fifteenth century is long gone through the “hazards of time,” yet the cloth has survived “almost unscathed.”

“Frustratingly,” concludes this brilliant writer, “the Shroud has not yet fully proven itself to us — not uncharacteristic of the Gospel Jesus, Who at certain times seems almost deliberately to have made His Presence obscure, as in His post-Resurrection appearance to Mary Magdalen when she mistook Him for a gardener, and His walking, shortly after, as an unrecognized stranger with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus.

“But one cannot help feeling it has its role to play, and that its hour is imminent.”

+

[resources: Tower of Light]