Our minds are on snow but let’s remember the hurricane season, which has now officially ended: Three category-five storms, one of the most powerful hurricanes ever recorded, zero U.S. landfalls, and a mystifying lull at the usual peak of activity. Together, these and other factors made for a “screwball” season.

“Fewer hurricanes formed, but of the five that did — Erin, Gabrielle, Humberto, Imelda and Melissa — four were considered major,” noted secular news.

That only tells part of the story.

The future will tell the rest.

We long have warned that, in these topsy-turvy prophetic times, with signs aplenty, we will not just see more category-five storms but that they may reach sizes and windspeeds that are unprecedented (at least in recorded meteorological history).

Call them “mega-hurricanes.”

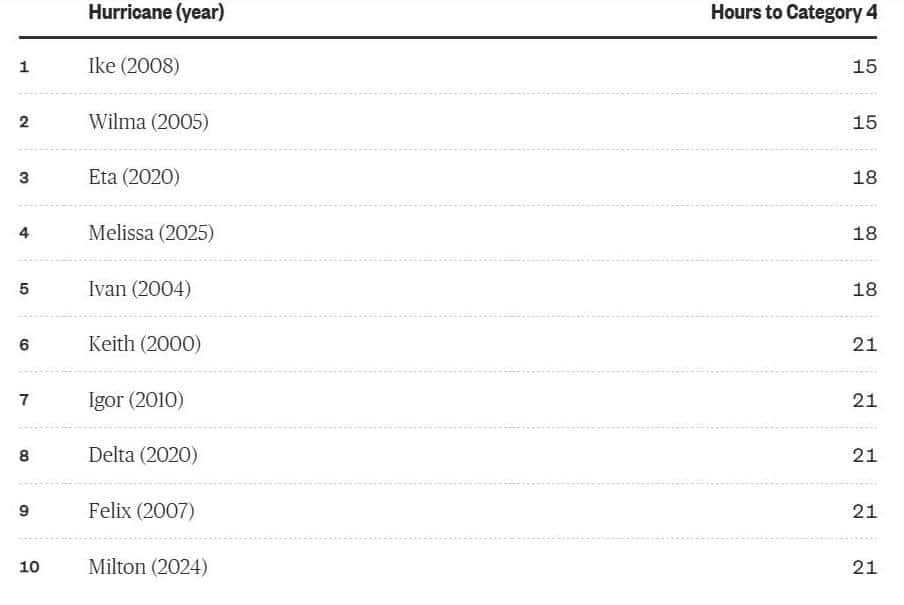

Hurricane Melissa’s wind gusts reached a record-breaking speed shortly before the storm made landfall in the Caribbean last month, according to data recorded during the deadly event.

One weather instrument called a dropsonde used during Hurricane Melissa clocked a wind gust of 252 miles per hour shortly before falling into the ocean.

A category-five is the highest rating on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, indicating a hurricane with sustained winds of 157 mph or higher.

This level of intensity causes catastrophic damage, including the destruction of most framed homes, total roof failure, and power outages lasting for months.

Can you imagine if this would have hit the U.S. mainland? (“Katrina’s” top wind speed was 174—about eighty mph less than “Melissa.”) Courtesy NBC:

As stated in Sent To Earth: “Great storms were coming in whatever direction the thermometer swerved but especially if more heat was pumped into the system.

“No one knew the full story but besides the cycle lasting two to four decades and involving temperature, ocean currents, and stratospheric winds, there was also the distinct chance that the ancient cycle of hurricanes a magnitude higher than even the highest current category (call it “category-six”) was kicking in.

Was the Middle Ages, so similar to what was now going on, going to repeat itself in this regard also?

Were we going to see the kinds of storms that had been seen in the medieval warming, and before that in the Bronze Age?

If so it meant hurricanes the likes of which we can only imagine, and it wasn’t just a product of climate. The forces were more mysterious than that. They operated in a way that transcended science. And it was a true use of the word awesome. There were indications that in the past storms had hit with surges twice what was seen during Andrew, up to forty feet, inundating a vicinity near Naples, Florida.

“From the historical record there’s evidence of some extreme hurricanes that hit this state from A.D. 800 to 1400 in the last global warming period,” I was told by Erle Peterson of the Dade County emergency office. “There’s a classic work where they found a Calusa Indian village on Marco Island in Collier County that was buried underneath a twenty-foot sand dune.

“The thing that was unusual is that everything was intact like a Pompeii event. The sand was put there, as near as they can tell, all at one time. And the only thing that could put a twenty-foot sand dune there all at one time is a storm surge.”

Although some claimed the sand was a remnant of ancient Indian burial mounds, Peterson argued that burial mounds contained skulls (which were detached from the body) and broken pottery (which had been ritually shattered when no longer used), where these heaps were not layered and contained unbroken pottery and whole skeletons.

It was as if something huge and unexpected had come upon them.

And Peterson believed that something had been a “hyper-hurricane” with sustained winds of 250 to 260 miles an hour.

Sustained winds, not just gusts.

Is that what we might see in upcoming seasons?

It was in the milieu that would compose or usher in chastisement. And it was coming. That was my take on it. The question was when, where.

While there was an increasing chance of a big storm heading north, all the way to New York or Cape Cod (where a scientist I interviewed named Kam-biu Liu of Louisiana State University reported indications of major storms in ancient times), and while Pacific hurricanes were beginning to circle close to California (as had a monster named “Linda”), the key threat, the nail biting, remained on coastal land from Cape Cod to New York to Virginia to Florida. Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.

Houston was three times likelier to get the big one than New York and Florida half-again likelier than Texas.

And as we have already seen, that was by no means the most powerful storm that could hit Florida. Where the devastating storm “Andrew” blustered with winds that may have gusted to 200 miles an hour, there were simple calculations that presented the ingredients for a much more terrifying storm. Scientists in England told me they expected a twenty-five percent increase in top winds with projected warming while at Princeton calculations called for an increase of up to 12 percent.

If we apply projected sustained winds of at least 230 to 250, gusts would head into the category of a major tornado.

At the same time, the mega-storm would be massive. Where “Andrew’s” swath was only thirty miles, winds of hurricane force could extend more than a hundred miles from a major storm and possibly up to two or three times that (600 miles).

The eye alone could be larger than “Andrew.”

Meteorologists know the big one — the really big one, greater than Andrew — is out there somewhere in the heat quotient of the ocean.

There were hurricanes like “Gilbert” (1988) that had been just as powerful as “Andrew” (1992) but many times larger, and a Pacific typhoon named “Tip” had the gale-force winds with a radius of more than 600 miles.

Florida was what famed hurricane expert Dr. William Gray described as a “sitting duck, a recipe for disaster.”

Monster hurricanes were brewing, and if it followed other trends, there would be quiet years followed by ones that were explosive. Were the ancient storms, the hurricanes thought by some to have caused ancient Aztecs to flee shorelines, that had once ravaged Peru, coming back?

“I’ve told people I would never write this because it wouldn’t be believed, but I’m going to anyhow,” said another whose home, save for his library, was trashed, Howard Kleinberg, former editor of The Miami News. “Only one book was ruined by ‘Andrew.’ It was in the front bedroom and it had been flung to the floor from a desk top to be soaked when the roof came apart over it. It was the Holy Scriptures. And to make it more unbelievable, it was open to that part of Genesis dealing with Noah and the Great Flood: `And God said unto Noah, the end of all flesh is come before me; for the earth is filled with violence through them; and behold, I will destroy them with the earth.'”

–MHB

[resources: Sent To Earth and Future Events]