How is it — how, pray tell, could it be — that the Vatican allowed a major Mafia gangster to be entombed at one of its own properties, Sant’Apollinare Basilica, in Rome?

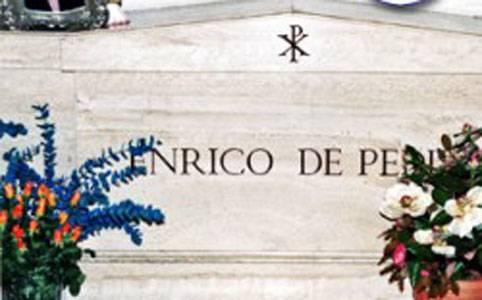

De Pedis was ambushed and murdered by former colleagues in 1990, himself a reputed murderer with numerous notches in his belt.

The series, at times Vatican-unfriendly, focuses one of its parts on De Pedis because it turns out the gangster funneled money, for “laundering,” to Banco Ambrosiano, a Rome financial institution with deep ties to the Vatican Bank — which allegedly sought to secretly funnel millions for the Polish freedom movement, Solidarity (led by Lech Walesa).

When the Banda della Magliana grew frustrated that its “loan” was not being repaid, goes one theory, it abducted the girl, 15-year-old, Emanuela Orlandi, in an effort, in essence, to blackmail the Vatican. She was last seen entering a green BMW after music lessons a distance from the Vatican — near Sant’Apollinare Basilica — and has never been found.

If that isn’t mysterious enough, a year before, the head of Banco Ambrosiano, Roberto Calvi (“God’s Banker,” below, left), was found hanging in London. His body dangled from the ironically named Blackfriar’s Bridge — a span named for the monks in black robes who used to reside nearby.

It’s suspected that it was

Among other intrigues: the bank was linked to a Masonic Lodge and a prominent cardinal, Paul Marcinkus, who had been embroiled in previous scandals and was the one orchestrating the reported transfer of money to Solidarity, for its fight against Communism.

Much can be and has been written of this, but the question, for now, is exactly why the gangster was allowed not just a Catholic burial, but a very special, church entombment.

And of course the answer — repayment for a favor — seems apparent.

Go no further than Wikipedia: “According to the former Banda della Magliana member Antonio Mancini, speaking in 2011, this was a reward to De Pedis for his role in persuading other members to stop the strikes (including Orlandi’s kidnapping) that the gang was making against the Vatican in order to force the restitution of large amounts of money they had lent to the Vatican Bank through Roberto Calvi’s Banco Ambrosiano.”

Eventually, in June of 2012, the gangster’s corpse was removed from the church and cremated, the ashes dissolved in the sea. But incredible it is that the burial at Sant’Apollinare Basilica ever occurred.

It’s a church that was founded in the early Middle Ages (possibly the 600s) using stone repurposed from imperial ruins, a minor basilica listed in the Catalogue of Turin as a papal chapel.

In 1990, Sant’Apollinare Basilica was granted to the Opus Dei, and is now part of their Pontifical University of the Holy Cross. One can see how the imaginations of anti-Vatican writers such as Dan Brown (The DaVinci Code) run wild.

Fascinating in the series is speculation, by secular journalist, Andrea Purgatori (who helped produce it) on what he sees as a link between all these events and the Fatima secrets.

Saint John Paul II was hospitalized, of course, following the attempt on his life by Mehmet Ali Ağca, on May 13, 1981 — anniversary of the first apparitions of Mary at Fatima. It is the theory of Purgatori (a name that also rings of a certain irony) that while recovering in the hospital, and studying the secrets, which he ordered brought to him in light of the Fatima date, the Pope discerned that he was the “bishop dressed in white” (gunned down in the third secret) and had to take action.

Did that action include financing Lech Walesa?

Other parts of the secret mentioned atheism and Russia, warning that unless consecrated to her Immaculate Heart, and unless there was practice of the First Saturdays devotion, this nation would spread its “errors” around the world.

Purgatori believes that preventing those errors was what prompted the saintly Pope to work closely (and allegedly, at times, secretly) to defeat Communism in Europe — which was miraculously accomplished.

But it wasn’t chiefly by way of money that Communism collapsed. John Paul II was a man of deep prayer (reportedly seven hours a day), and his focus, after the shooting, most likely was on the Fatima request for consecration.

For not long after the shooting, the Pope conducted just such a consecration (of the world to Mary’s Immaculate Heart, implicitly including Russia). That, according to Sister Lucia, is what brought down Communism and prevented what she said would have been an “atomic war in 1985.”

[resources: Michael Brown online retreat Saturday, 10/29, 11 a.m. EST]