![]()

By Michael H. Brown

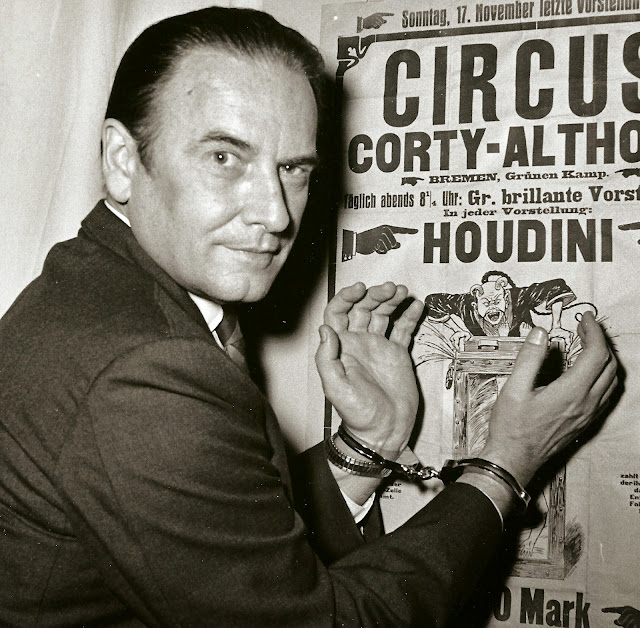

In the 1970s, while a cub newspaper reporter, I was assigned to attend the anniversary of magician Harry Houdini’s death. It was held, each year, at the Harry Houdini Museum in Niagara Falls, Ontario — on Halloween, which is the day the famous showman died.

There I met the president of the Society of American Magicians, Melbourne Christopher, the world’s foremost expert on occult trickery. Later I briefly joined the society so I could learn some basic tricks used by spiritualists, for I was researching supposed psychic phenomena and wanted to see what was “real” and what was fake.

The point is: Houdini, who remains an enigma, even to fellow practitioners of legerdemain. How was it, for instance, asks Smithsonian Magazine recently, that back in 1908, at the Columbia Theater in St. Louis, “the great master of illusion stepped inside of an over-size milk can, sloshing gallons of water on to the stage.

“The can had already been poked, prodded and turned upside down to prove to the audience that there was no hole beneath the stage. Houdini was handcuffed with his hands in front of him. His hair was parted down the middle and he wore a grave expression on his face. Holding his breath, he squeezed his entire body into the water-filled can as the lid was attached and locked from the outside with six padlocks. A cabinet was wheeled around the can to hide it from view.

“The can had already been poked, prodded and turned upside down to prove to the audience that there was no hole beneath the stage. Houdini was handcuffed with his hands in front of him. His hair was parted down the middle and he wore a grave expression on his face. Holding his breath, he squeezed his entire body into the water-filled can as the lid was attached and locked from the outside with six padlocks. A cabinet was wheeled around the can to hide it from view.

“Time ticked away as the audience waited for Harry Houdini to drown.

“Two minutes later, a panting and dripping Houdini emerged from behind the cabinet. The can was still padlocked.

“During his lifetime, nobody ever managed to figure out how he had escaped.”

As it turned out, Houdini was more an ingenious inventor than even a master of stage stunts. I don’t know how he did the milk can trick, but there were gimmicks he created that released all straps to which a person was tied (in this case, to a cross) with a simple and slight movement of the foot.

As it turned out, Houdini was more an ingenious inventor than even a master of stage stunts. I don’t know how he did the milk can trick, but there were gimmicks he created that released all straps to which a person was tied (in this case, to a cross) with a simple and slight movement of the foot.

There’s all that — the escape artistry.

And then one looks at magic, which derives from tales of ancient occult powers.

Houdini claimed he didn’t believe in the supernatural — and said if the afterlife existed, he’d contact the living when he died (as if he would have a say over the matter, once he passed).

That was part of that anniversary celebration: a mock “seance,” at the museum in Canada, though the participants didn’t really believe anything would happen (and didn’t). They were doing it as a joke (and to get newspaper publicity from reporters like myself).

That was part of that anniversary celebration: a mock “seance,” at the museum in Canada, though the participants didn’t really believe anything would happen (and didn’t). They were doing it as a joke (and to get newspaper publicity from reporters like myself).

Unwittingly, however, Houdini and other magicians were and often are vicariously in touch with the forces they sought to dismiss. We can see that in their eyes.

They play with fire — occult images, locations, and paraphernalia. There is often an evil edge. Escape acts derive from spiritualist history, notes one modern magician, Raymond Teller. In the mid 19th-century, mediums not only claimed to communicate with the dead but worked miracles. “In seances, mediums were typically restrained in some way,” he pointed out. “At least tied and sometimes chained or handcuffed.” Houdini followed in their footsteps, though claiming nothing supernatural.

“[The spiritualist performer] would escape to do their manifestations and get locked up again,” Teller told the magazine.

Houdini campaigned against frauds, and frauds there were — fake “mediums.”

Were they all — or were some tapping into an actual power, a dangerous, occult one?

Geller could tell what someone was drawing by watching the top of the pen or pencil, Melbourne, who was a big Geller skeptic and critic, told me, or did so through some other trick.

What neither Geller nor any magician could do, Christopher said, was send such a mental image. In that case, the only person cheating would be the receiver (in this case, me).

I did as told when I met Geller, who agreed to draw something and then mentally send it to me. He sketched it and folded the paper and handed it over. I tucked it under my leg, closed my eyes, and immediately, as if formed in lightning, “saw” a Christmas tree with three ridges on each side, disconnected on the right from the trunk.

When I opened the piece of paper Geller had given me, and that I had been holding, it was absolutely precisely that — right down to the disconnected trunk.

There was no way that anyone could do that, Christopher had said. There was no trick. He had been certain Geller would fail. Though Christopher and other magicians sought to prove Geller a fraud

But back to Houdini:

This wasn’t just a guy pulling rabbits out of a hat! While hidden “detaching” panels and rope-slicing blades have been found in some of Houdini’s surviving inventions, most of his secrets, even 90 years after his death, on October 31, 1926, from complications of appendicitis, have remained just that—secrets.