A fascinating aspect of the tragic (please pray for the families) collapse of that condo tower in Miami: the fact that for years, residents had complained of water in the parking garage.

It wasn’t a case of rain, periodic puddles, or drips of condensation from concrete, but often one or two feet of water, and not just any water, but salt water. It came when there were especially strong tides from the ocean.

For years now, sea levels have been on the rise, obscured by often unfortunate political flak. But no partisan issue, this: NASA’s climate division — under presidents of all flavors — since 1995 has measured a rise on global seas of 97 millimeters, which is nearly four inches, and twice that in Florida.

That may not sound like much — inches — but averaged over the globe, and for low-lying places, it is a fearsome lot.

The earth is trapping twice as much heat as in 2005 — what Pope Saint John Paul II called the “greenhouse effect” (when carbon dioxide acts like a magnifying glass, intensifying rays from the sun, as the sun itself — quite autonomous of human effects — may be changing).

“Faced with the widespread destruction of the environment, people everywhere are coming to understand that we cannot continue to use the goods of the earth as we have in the past. (…) The gradual depletion of the ozone layer and the related ‘greenhouse effect’ has now reached crisis proportions as a consequence of industrial growth, massive urban concentrations, and vastly increased energy needs. Industrial waste, the burning of fossil fuels, unrestricted deforestation, the use of certain types of herbicides, coolants, and propellants: all of these are known to harm the atmosphere and environment. The resulting meteorological and atmospheric changes range from damage to health to the possible future submersion of low-lying lands.”

Tides are higher, storm surge is more severe, and there are islands, such as Maldives, that are literally disappearing.

Again, it’s not a matter of debate when the land around you is slowly gnawed away by the ocean.

Ditto for the Marshall Islands.

On the tropical island of Tuvalo, the highest point is a mere four and a half yards above sea level. That’s also true of many coastal communities in the U.S.

In Miami, residents and officials alike have time and again seen what they call “sunshine flooding,” seawater that collects on streets — and in garages — without there having been a storm. It is tidal — seawater finding its way through porous rock and under sea walls — and that’s what residents at the collapsed condo said of the garage, that saltwater intrusion corresponded with what are known as “super tides.”

Did that water corrode underground supports and the garage there, causing or contributing to the tragedy? And what about thousands of other structures along the oceans, many within a stone’s throw of cresting waves?

In Florida, for years communities have been slurping up groundwater from wells as a drinking source, for industries, and especially manicured lawns. As the groundwater recedes, saltwater fills the “vacuum.”

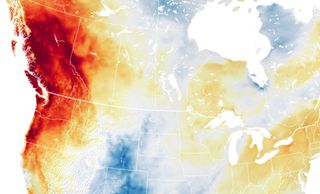

It joins other gradual but momentous events, such as the mega-drought out West, along with bizarre spikes in temperatures, such as the 121 degrees recently experienced up in Vancouver — Vancouver! — Canada. That comes curiously at the same time that churches there are being set afire by arsonists upset over alleged school abuses there. Chastisements often develop over time. The bubonic plague in the 1300s peaked over a span of six years and recurred for many decades, and mega-droughts can last for centuries (beware, California). In one place, not enough water. In another, too much.

We thus see how a sign of the times, how warnings, how a chastisement, can come in slow but excruciating motion — with occasionally punctuated events, like perhaps (and at this stage, only perhaps), that ill-fated Surfside tower.