How many times have we discussed the weather?

And now more than ever.

If it isn’t Lake Mead, the Po River, and the Great Salt Lake evaporating, or an emergency warning in England, with temperatures expected to hit 104 degrees (hottest ever, in a country with a long recorded past, and no air conditioning), then it’s the Bridge of Nero popping up in Rome as the level of the Tiber River retreats.

Hard to imagine that something isn’t going on.

And then, there’s the hurricane season.

We’re entering what’s usually the intense period of it.

So far, so good: Perhaps forecasters will be wrong this annum (they see a very active season). But every summer, our thoughts and prayers turn to states like Florida, Texas, and Louisiana.

In Florida of course is the booming city of Miami — with a metro area now of 6.1 million (ninth in the U.S.). That’s music to a realtor’s ears but of massive concern to hurricane experts, who years ago, going back to 1999, told us that a city should never even have been built there, that it’s too much in the path of potential danger.

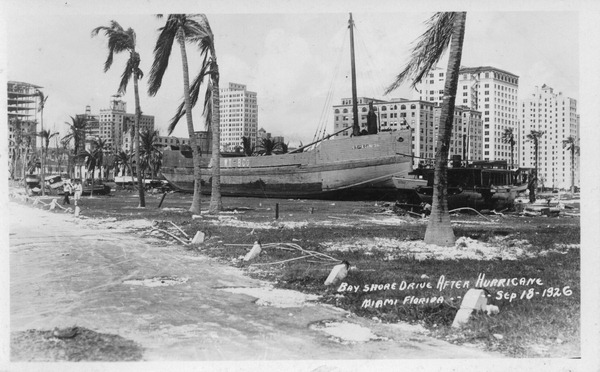

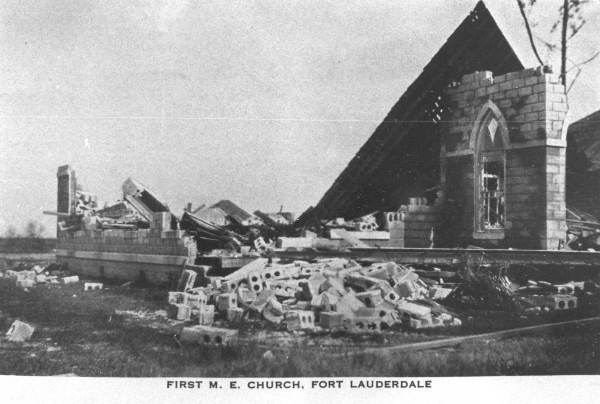

One must recall that Hurricane Andrew — one of the most vicious storms in history, in effect a gargantuan tornado — just missed Miami, steering to the south at the last moment, and that in 1926, when the city had a population of just a hundred thousand, it wasn’t as lucky, suffering catastrophic damage.

When we spoke to hurricane experts one said he recalled a storm whereby whitecaps were seen where ritzy homes now stand in Coconut Grove. They would have been underwater.

If the 1926 hurricane hit today, there would be an estimated $250 billion (as in a quarter of a trillion) in damage.

At the height of the storm surge, the water from the Atlantic extended all the way across Miami Beach and Biscayne Bay into the City of Miami for several city blocks.

Notes Accuweather, which ranks the city as most storm-vulnerable in the U.S., “Miami takes the number one spot on this list with a 16 percent chance of experiencing the impacts of a hurricane in any given year.” And storms seem to be getting larger and more intense.

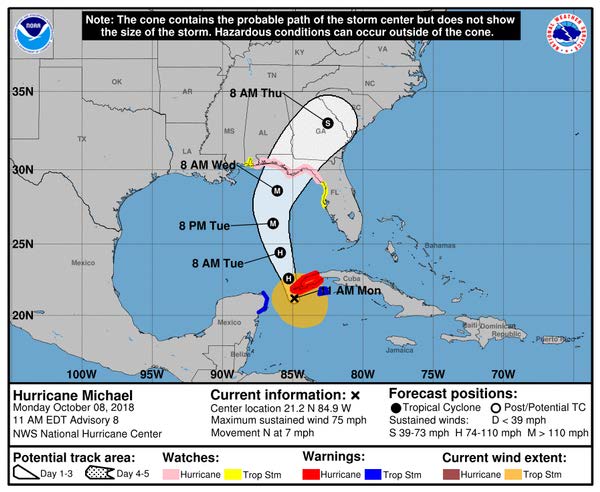

The question every year: What if a category-five, like “Camille” or “Michael” (2018), made a direct hit?

(The 1926 cyclone was a category-four.)

Note: a casino.

“Based on historical data, on average a hurricane will pass within 50 miles of the Miami metropolitan area every six to eight years,” said Accuweather. “With the Atlantic Ocean to the east and a maximum elevation of 42 feet above sea level Miami’s geography makes it highly vulnerable to hurricanes. In addition to this, a majority of the population resides within 20 miles of the coastline increasing the risk of high property damage.”

Due to rising seas, there are now tidal floods in the area even when there aren’t any storms. Yet, new apartment complexes and office buildings, many housing investors from New York, are under construction. Cranes accent the skyline. “Led by Mayor Francis X. Suarez,” says the Wall Street Journal, “Miami is attempting something so ambitious it has rarely succeeded anywhere before—transforming a city identified with glitzy beaches and nightlife into a world-class business and financial center.”

Many don’t realize the apocalyptic damage Hurricane Michael wrought on the panhandle just a few years ago because it was largely in rural areas — turning shores into dilapidated metal and wood and forests into moonscapes.

There was damage to 2.8 million acres. We wove in and out of the felled forests for hours.

The 1926 hurricane not only brought the Florida boom to a screeching halt, but has been noted by some as an early omen of the Great Depression.

If a hurricane of that force hit, it would be one of if not the greatest natural disaster in recorded U.S. history and once again call to question the very existence of such a large metropolis in its current location.

The same question is asked of cities such as Naples, Palm Beach, and New Orleans

+