Is there really any way to deny it any longer — the authenticity of the Turin shroud, burial cloth of Our Lord?

The answer is a resounding “no,” though of course there are those, of secular bent, who dismiss it out of hand.

They do so without facts on their side. The facts are with those who believe.

And those facts keep piling up.

It was back in 1988 that skeptics had their day: release of a study purporting to show the Shroud of Turin was a medieval “forgery” dating back only to the 15th century or thereabouts (1360 to 1490). The “news” was trumpeted by media such as The New York Times, which had it on the front page. Even the Church acknowledged the study.

It was their “Aha!” moment.

But that study was based on radiocarbon dating. Unfortunately for scoffers, the technique, now antiquated, has since been found to be badly flawed.

A fire that scorched a bit of the cloth in the 1500s could have skewed the results (fire creates carbon), and with or without flames, microbes exude substances that cause flawed radiocarbon readings.

Some assert the radiocarbon testing wasn’t even done on the original Shroud material itself, but on a patch inserted as a repair in more recent centuries (yes, in the Middle Ages).

More recent and reliable dating places the date smack where it belongs: approximately two thousand years ago, at the time of Christ’s Crucifixion.

That’s one aspect of authenticity.

There’s more — much.

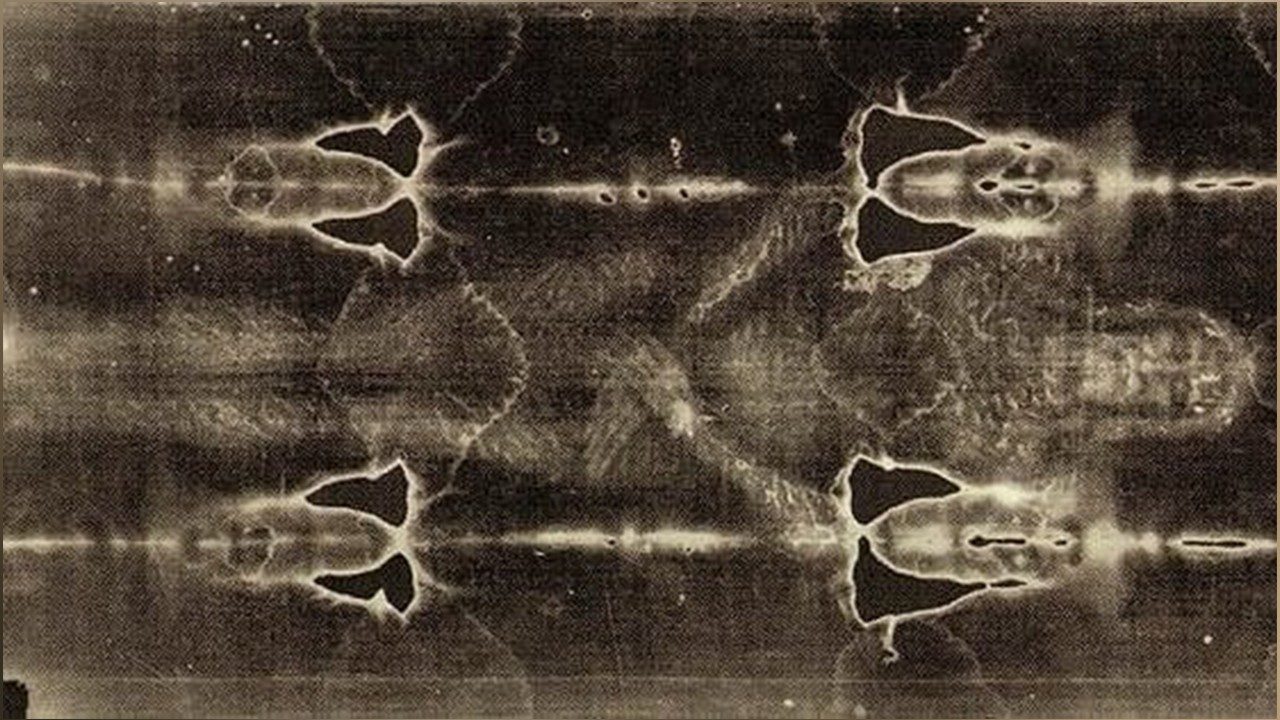

Start with the fact that, astoundingly, details of the vague image on the Shroud weren’t even discovered until 1898, when a lawyer and amateur photographer named Secondo Pia took a photo and upon developing it was shocked to see an actual photograph (not just outline) of a man [see below, left and right].

In other words, the Shroud was a negative, and a negative of that negative gave him a positive.

That fact had been hidden for 1,900 years and alone excludes the possibility of forgery.

No one in the Middle Ages could have anticipated the techniques of modern photography (or photography period).

As is the case with the image of the Virgin Mary at Guadalupe, Mexico, to this day no one can explain the technique that placed the image — full body length of Jesus, front and back — on a stretch of cloth.

“Recently, the shroud cloth has been dated by four new methods that have not been as well publicized as carbon dating,” says Dr. Gilbert Lavoie, author of a new book, The Shroud of Turin. “From the analysis of the first three different methods combined, the final date of the shroud cloth calculates to 33 B.C., plus or minus 250 years.”

The most recent test — the fourth — is an x-ray technique, notes the author, that puts the Shroud’s age at 55 to 74 A.D.

If that’s not getting precise enough — bringing us right to the year we would expect — there are the pollen and spore studies.

They indicate flowers and mold are present on the linen, plants that indicate an origin in the Middle East and particularly, Palestine.

Jerusalem was the most central and significant city in ancient Palestine.

It also, of course, is where Jesus was crucified, wrapped in the linen cloth, and entombed before He was resurrected. (All glory!)

Remarkable is the precision with which more than five hundred types of plants have been identified from the pollen extracted from the Shroud — some of them not most associated with Palestine but with the very vicinity of Jerusalem itself.

Most amazing has been the work of Botanist Avinoam Danin of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem: Danin’s analysis suggested that flowers and other plant materials were placed on the Shroud of Turin, leaving not only pollen grains but the imprints of plants and flowers on the linen.

Notes Science Daily, “Tentatively identifying the plant images through a method of image comparison known as Polarized Image Overlay Technique (PIOT), [scientists] Alan and Mary Whanger have reported that the flowers were from the Near East region and that the Shroud originated in early centuries.

“Analysis of the floral images by Danin and an analysis of the pollen grains by Uri Baruch identify a combination of certain species that could be found only in the months of March and April in the region of Jerusalem during that time.”

“This combination of flowers can be found in only one region of the world,” Danin stated. “The evidence clearly points to a floral grouping from the area surrounding Jerusalem.”

You are excused if you’re already ready to say, “Case closed.”

But there’s more.

And it takes you right to the Crucifixion — and, perhaps, the Resurrection itself, for that’s when some kind of unrecognized energy that can’t be duplicated even with the most advanced infrared and laser caused the image on the Shroud, which has been proven not to have been made with any paint, stain, or tincture.

Besides pollen and dating, there are blood marks: the Shroud’s are type AB — like the sudarium of Oviedo in Spain (reputedly Christ’s facial burial cloth).

And when enhanced with ultraviolet light, those marks are often in pairs and are dumbbell in shape — exactly like the horrible scourging whip known as the Roman flagrum.

No one knew this during the Middle Ages.

(The first flagrum wasn’t even discovered until the 1700s).

On the Shroud, the thumbs seem to be missing from the hands.

Meanwhile, the scourge marks of the upper back are wider than others, suggesting that this was the result of a heavy load on the shoulders!

It also has been shown that those blood marks — and there are many of these (bringing to mind the gruesome statues popular in South America) — preceded the outline of the Man (the fibers under the marks are white, while the fibers under the image are yellow, which was produced by an oxidative process).

Thus, one can deduce, yes: first the Blood (crucifixion), then the energy caused by His Resurrection.

“For a painter to have created this image, he would have needed a paintbrush the size of a fiber which is less than half the width of a human hair,” note another scientist, Dr. Alan Adler, a chemistry professor in Connecticut.

Instead, points out Dr. Lavoie, it is more like “intense bursts of vacuum ultraviolet radiation.”

This is a scientific book, yes; but it is one that brings the reader right there to Calvary and the Tomb.

[resources: The Shroud of Turin]

+