We realize the Second Vatican Council threw the Church into much tumult — that what was intended to be good was used by certain elements to implement modernism. Not good.

But one positive fruit from that era — rarely mentioned — is critical in our time: late priesthoods. Men who have “second-career vocations.”

Without them, many churches would be without priests — and without priests, obviously, there is no liturgy.

We were prompted to consider this at Mass last week by a local second-career priest who expressed gratitude to John XXIII for making late-vocations possible.

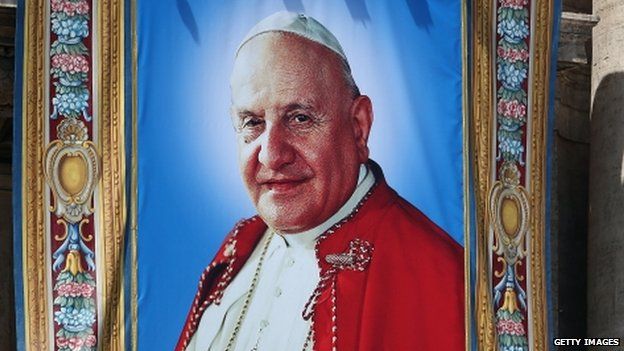

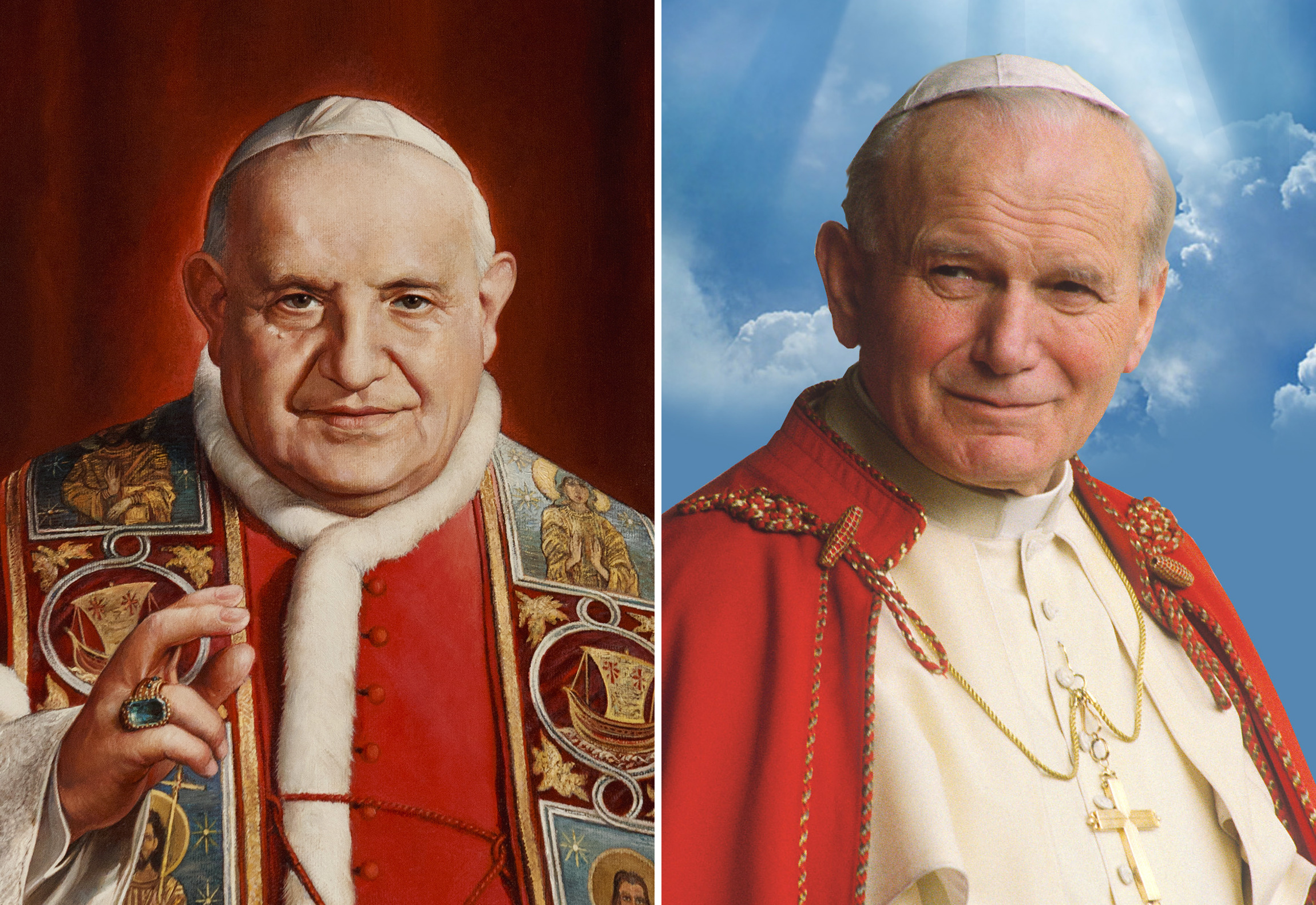

Like the current pontiff, Saint John XXIII (whose canonization, along with that of the great John Paul II, we attended), remains one of the most influential, endearing, and yet at the same time controversial figures in the annals of Catholic Church history.

His papacy, though relatively short (from 1958 to 1963), left an indelible mark on the Catholic Church, particularly with the convening of that Vatican Council.

But a far less discussed aspect of his leadership was his emphasis on vocations, and notably, late ones.

His move came at just the right moment. A survey of seven dioceses around the world (by The Pillar) indicates that from the 1950s to 1961, the number of diocesan ordinations in those seven sees decreased by twenty-eight percent — from an average of 12 annual ordinations per one million Catholics during the 1950s to nine in 1961, the year before Vatican II was called.

More declines in vocations, it seems, followed the Second Vatican Council: The number of priests ordained per million Catholics declined another fifty percent in the two decades following Vatican II.

“It was his pastoral nature and openness that saw the value in late vocations. He recognized that life experience, maturity, and prior secular knowledge could enrich one’s spiritual journey and offer a unique perspective on religious life,” we are told in another commentary.

“In a world rapidly changing due to technological advancements, geopolitical shifts, and social upheavals, John XXIII realized the need for a Church that could respond adeptly to modern challenges. By embracing those with late vocations, he believed the Church could tap into a reservoir of experience and wisdom that younger seminarians might not yet possess. This is not to devalue the enthusiasm and vigor of youth but to recognize the complementary strengths that older individuals can bring.”

John XXIII’s openness to late vocations had several profound impacts:

Diversity of Experience: By welcoming those who had pursued other careers or life paths, the Church benefited from a wider array of experiences. Former doctors, lawyers, teachers, or even laborers could bring their unique insights into their pastoral roles, enriching their ministry.

Mature Leadership: Older individuals often come with a depth of life experience that can be invaluable in pastoral care, counseling, and leadership roles within the Church.

Addressing Shortages: During certain periods in the Church’s history, there have been shortages of priests and religious. By being open to late vocations, the Church had another avenue to address these shortages.

Renewal and Reformation: John XXIII was deeply committed to the aggiornamento (updating) of the Church. By allowing late vocations, he effectively introduced fresh perspectives, which played a role in the broader renewal efforts of Vatican II (often for the better, sometimes for the worse).

Saint Pope John XXIII: often in the shadows of memory but nearly an amalgam of his successors.

Shades of Francis:

Shades of Benedict:

Shades of John Paul II:

with whom he was canonized:

While the question of vocations – late or otherwise – is multifaceted, John XXIII’s legacy serves as a reminder that the call to serve can come at any stage of life, and the Church is richer for it.

[resources: Michael Brown retreat: the Church, the times, Saturday, October 21, 11 a.m. EST, videotaped for those who choose to view it at their convenience]