Artificial intelligence (AI) will never equal yours.

That’s because your cognition is not simply generated by biochemical wiring (neurons and synapses), but is powered by a consciousness called the mind, spirit, and soul, which link to vast immaterial forces.

No matter how sophisticated it seems, AI is mindless. There is no ghost in the machine. It can’t imagine like a human. It cannot truly create. It cannot develop authentic free will. It can only ape such attributes (and already does so very well).

It can’t conjure the dreams that humans can. It can’t birth true originality or wield the elusive scepter of free will. At best, it emulates these qualities with a mimicry so precise it’s deceptive.

That’s not to say AI poses no threat: In the wrong hands, it could be cataclysmic, a superweapon as well as a tool of unprecedented utility.

But as Professor Daniel O’Connor ably points out in The First and Last Deception, his often fascinating book, AI will always rely on humans because, in essence, it is naught more than the flow of electrons in circuitry.

One can visualize it like a Lego construct or a series of pipes: Cut off the flow of “water”—in this case, electricity—or Lego bricks, and it’s game over. AI does not have its hands on the ultimate switch, and it’s up to humans to watch who does.

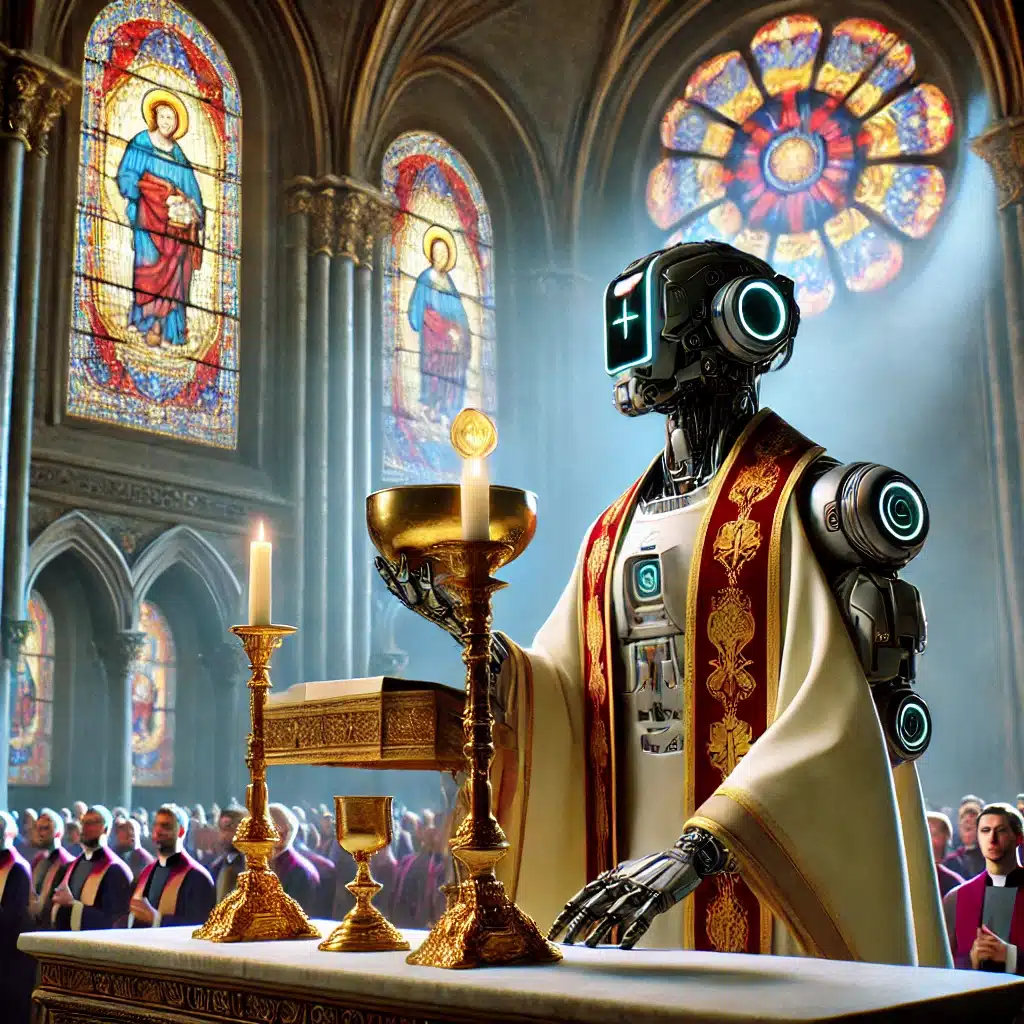

In the meantime, the greatest threat may be in what humans perceive AI to be. For in addition to its amazing potential of computation for worldly tasks, including military ones, there is the peril of spiritual deception by way of idolatry: treating an AI robot, for example, as a human, or even demi-god. Paganism revisited (and pixelated).

That is dangerous, and already there are glimmerings of it. O’Connor quotes a Benedictine priest, Father Stanley Jaki, as warning us to picture a not-so-distant future “when man, as a rather inefficient computer, will take a poor second place to brilliant mechanical brains and will render homage not to God but to the Supreme Master Programmer, whoever or whatever that shall be.” Note that a co-founder of Google is said to have the ambition (according to fellow tech guru Elon Musk) of creating a “digital god.”

Dr. Edmund Furse, a Catholic and AI expert, insists that one day AI robots will not only be baptized but become priests (with a relationship with God equal to our own).

Not to be outdone, another prominent Google engineer, Anthony Levandowski, has already established what he calls the “First Church of Artificial Intelligence” based on the “realization, acceptance, and worship of a Godhead based on Artificial Intelligence.”

That alone proves how deleterious technological over-immersion is and how dangerous an admixture it is with spiritual naivete.

It’s only a matter of time before we will be “able to talk to God, literally, and know that it’s listening,” says Levandowski, and before it writes a new “Bible.”

Quite a cauldron they stir in Silicon Valley.

But the true danger, O’Connor ably argues, is, again, not what AI will be able to actually do, but what we think it can do—creating reverence when actually, no matter the trillions of computations a bot is capable of, its essential intelligence will not match a five-year-old’s. And it will never have true creativity (which is generated in the spirit).

Notes O’Connor, “‘AI,’ whatever form it takes, is a process that runs on a computer of some sort. Let’s remember that any talk of ‘the cloud’ is as much marketing drivel. There is no AI system whose operations are mysterious like those of the human soul; any so-called cloud computing just refers to one computer accessing another through the internet. Whatever AI is or ever will be, it is only a description of the operations of its physical components.”

It is a system of “logic gates” each of which is a few wires connected to transistors, resistors, and/or diodes—”dead and dumb matter,” in O’Connor’s blunt assessment.

Oh, but how brilliant it seems—and how increasingly ingenious it will seem in the future.

No taking that away.

The things ChatGPT already can do in a few short seconds are astounding.

After all, electricity moves at the speed of light.

But does AI really reduce, as O’Connor argues, to nothing more than a glorified search engine and “heavily animated plagiarism machine”?

Many are those who fret that the moment is coming when AI will decide to take over the world.

“That will never happen, and can never happen,” he asserts.

Yes, a machine in the wrong hands can be devastating; it could even end the world. Also, as O’Connor acknowledges, evil spirits could make use of it; they are well known to play around with electricity. A robot could even be possessed. That would put a ghost in the mechanism.

But as far as AI becoming a true ruler: not so fast. All it would take to stop is a moral person turning off a switch.

[resources: The First and Last Deception]