How did the Church evolve from its earliest days, when its observances consisted mainly of meetings during which followers of Jesus shared a meal, read Scripture (or what would soon become the canonical Bible), and reflected on Him?

The story is long — 2,000 years long — so, in coming months, occasionally we’ll take a piecemeal approach to exploring it.

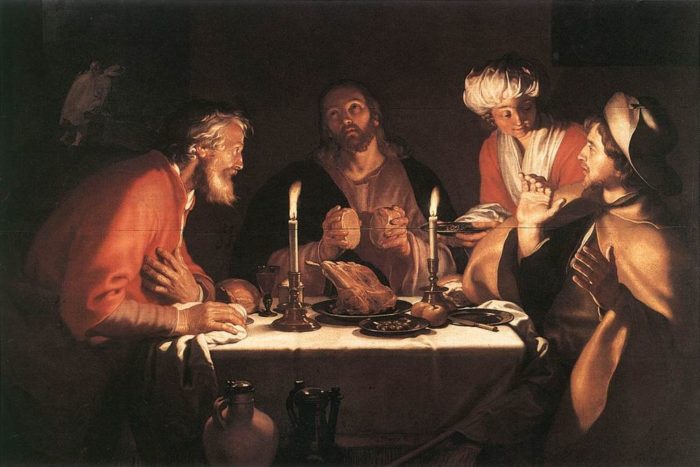

Today, one contemplates certain developments during the Middle Ages, specifically to do with Communion and Mass.

It was the time period when dioceses and parishes took clearer authority and form, bishops gained prominence (though this authority structure had been around since the first few centuries), and the rituals and sacraments began to change. Institutionalization of what for a long while had been a more spontaneous, casual affair had begun several centuries after Christ, when Christians were straying into esoteric practices such as Gnosticism (which was in some ways a precursor of New Age).

And so too were the clergy and what became known as the liturgy formalized, with increasingly strict, and no longer so spontaneous, guidelines.

As historian Charles Bokenkotter points out, “It was at Mass that the separation of clergy from people was made dramatically evident. While the Mass retained its basic meal structure, even in the early centuries it began to move away from its original character as an action of the whole community.

“This tendency intensified during the Middle Ages. The people were gradually excluded from all participation, and the Mass became exclusively the priest’s business, with the people reduced to the role of spectators.

“No longer were they allowed to bring up their ordinary bread for Consecration; the priest consecrated unleavened bread already prepared. Nor were they allowed to take [the unleavened bread] in their hands, standing as they once did; now they had to kneel and receive it on the tongue, while the chalice was withheld from them.”

We didn’t realize that kneeling for Communion on the tongue was so “recent.” We’re talking mainly about the 1100s to the 1300s and subsequent centuries. Few realize how the transcendental, mysterious, and highly formal nature of Mass evolved. Nor do most Catholics know how the priesthood changed over time. There were periods when celibacy fell into decay. There were also periods when only monks, nuns, and priests received Communion frequently. “The main object of the layman in coming to Mass was to see the consecrated wafer, which had for many the climax came when the priest elevated it after Consecration.”

Bokenkotter — a secular historian, not always very favoring of Catholicism — complained, in a book about the Church’s entire timeline, that community participation gave way to a more transcendental, awesome, mysterious, but separated and often aloof liturgy. In the future, we’ll explore how the very first “Masses” were conducted.

As Justin (114 to 165) wrote in his First Apology:

“On the day called Sunday all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen.”

Although, by the Middle Ages, Mass greatly differed from the first century, a specifically commissioned ministry long had been formed, a creed was drawn up long before (indicating that orderliness was not exclusive to the medieval times), and there was expanding formality: oh, the transcendental and mysterious: there’s something to be said for that!

+