During a recent interview with a New York Times columnist, Christian nationalist Doug Wilson, a Presbyterian Calvinist, in arguing for the return of Christianity in governance, remarked that “one of the things is that America was founded as a Protestant Christian country. At the founding we were 98 percent Protestant, in every direction.”

In other words, we should go back to that form of Christianity.

In the good old days, argued Wilson, before its descent into secularism in the Fifties and Sixties, Puritan Protestantism established a better version of the United States.

“When it came to it, America kept her Protestant ethos and incorporated successfully Catholics and Jews,” said Wilson. “That’s something that we know how to do. We’ve done it before—it’s been done. I’m grateful for that.”

And we should do it again, is his argument.

We’re all for Christianity, of course. (Remember when abortion and sodomy were illegal?)

But we have to remind Reverend Wilson that the first form of Christianity established in America was not Presbyterianism nor any form of Protestantism but Catholicism.

Remember Christopher Columbus? He was a third-order Franciscan and daily communicant who, like other early explorers, considered his main duty that of a missionary, visiting a Marian shrine in Spain and going to Confession before setting out on the dangerous journey across the uncharted Atlantic (on a flagship the Santa Maria).

See Where the Cross Stands, which says, “Fair of complexion, with freckles and an aquiline nose, neither pudgy nor rail-thin, with grey hair, on the muscular side, high of cheekbone, somewhat taller than average, with the carriage of an aristocrat, yet the sensibilities of a crewman, Columbus often had a monk’s cord around his waist and sometimes—not aboard, that anyone has reported, but after his famous expeditions—was seen in a monk’s robe, entertaining thoughts, at one point, of entering a monastery.

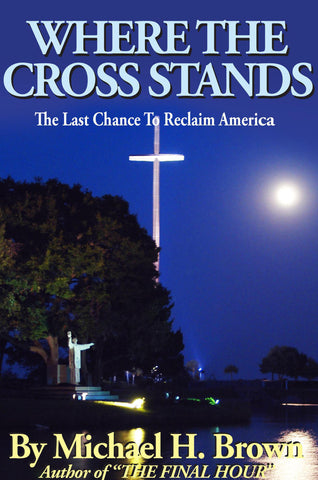

In St. Augustine, Florida, the oldest city in the United States, the tallest known Cross in the world stands on Matanzas Bay (above), marking the spot where the first documented Catholic Mass in the U.S. took place.

That wasn’t where Columbus landed but rather another Catholic explorer named Admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés.

“Surely there had been earlier Masses, explorers in previous years who were known to have priests aboard: adventurers who had reached places such as southwestern and northwestern Florida. But this is the official spot where—for all intents and purposes—Christianity entered America.

It stands two hundred and eight feet tall, does the Cross, erected there in 1966 as if to offset—or war against—the evil which entered the country that decade and especially that year,” says the book. “To stand under this Cross, which is located at what is now the oldest Marian shrine on the continent, is to feel Grace.” This spot, Mr. Wilson, dates back to the sixteenth century, long before Williamsburg, Virginia, and Plymouth Rock.

A unique, vine-covered chapel is dedicated there to Our Lady of La Leche, or “Our Lady of the Milk,” showing the Blessed Mother nursing her Child. Pregnant women come here to ask for safe deliveries, as do women seeking to become fertile, often finding those prayers answered.

“Some day in the future—perhaps the not-so-distant future—this Cross and this area may play a role in the spiritual and temporal survival and revival of America.

“It was on August 27, 1565, according to a priest’s own diary, that a marvel factored into the picture.

“It came at nine that evening when a comet suddenly blazed through the dark directly above the ship. According to the priest, all were astounded, for it gave ‘so much light that it might have been taken for the sun. It went toward the west—that is, toward Florida—and its brightness lasted long enough to repeat two Credos.'”

God, he wrote, “showed to us a miracle from Heaven.”

Back to Columbus: clerics who joined Columbus on subsequent voyages—Franciscans as well as Dominicans, and Augustinians—were soon aboard the ships of other explorers, including Ponce de Léon, who discovered Florida around Easter in 1513.

There are legends that Saint Brendan of Ireland landed in Greenland and that there had been a liturgy around 1112 A.D. (Greenland is technically part of North America). There are additional legends of Vikings setting foot as far south as Newfoundland and even Maine in those early years. At Kensington, Minnesota, a slab of soft calcite some believe was put there in the 1300s bore mysterious runic markings. If not a hoax, it meant that a century before Columbus (who during his second voyage had Mass celebrated at La Isabela west of the Dominican Republic), Vikings had etched the following:

“Eight Goths and 22 Norwegians on an exploring journey from Vinland very far west. We had camp by two skerries, one day’s journey north from this stone. We were fishing one day when we returned home and found ten men red with blood and dead. AVM [Ave Virgin Mary] save us from this evil. We have ten men by the sea to look after our vessel forty-one days’ journey from this island. Year 1362.”

If true, the Virgin had been invoked seven centuries ago in what is now the U.S.

We carry another book called The Final Hour.

That hour, though dwindling—despite the sand moving through the hourglass—has not yet concluded.

We have time.

We have minutes.

We as a society—and as a Church—can still rebound. We agree with you, Reverend Wilson.

We can still recover America. We’re at a “turning point.”

We can stave off “chastisements.”

We can turn morals around.

We can prevent the unraveling of society.

With prayer and fasting, we can stop wars; we can suspend the laws of nature.

With hope, we can succeed despite indications to the contrary—despite compelling facts indicating that the country has gone around the bend, that it is over the top, that it has passed the point of no return. There is still a chance. It is a prayer to say beneath this Cross. It is a prayer for anywhere.

But time is short, and in the near-distance, a trumpet sounds.

[Footnote: Remember these words from an alleged prophecy: “… I have ordained as a beacon of light… the place near the water where the Cross stands.”]